Halloween is not just a celebration of costumes and candy. It’s an ancestral ritual of confrontation — a moment when we collectively decide to face what we usually avoid: fear. But why? What human need is satisfied when we deliberately seek out stories that unsettle us, that make us question our safety, our sanity, or the very nature of reality?

Your must agree that fear is perhaps one of the most democratic and universal emotions. It crosses cultures, eras, and social classes. It serves obvious evolutionary purposes — keeping us alive — but also more subtle social and psychological functions. Horror stories allow us to explore deep anxieties in a controlled environment, function as rehearsals for chaos, and reveal the cracks in our everyday certainties.

So I decided to make a list of books and movies to revisit fear this halloween, but this list is not a simple enumeration of “horror classics”. It’s a map of different anatomies of fear: from cosmic horror that confronts us with our insignificance, to psychological terror that questions the stability of our minds; from monsters that represent the social anxieties of their time, to very human predators that remind us the real monster might be right beside us.

The Call of Cthulhu — H.P. Lovecraft (1928)

Lovecraft didn’t just invent monsters — he invented a specific type of terror: cosmic horror. “The Call of Cthulhu” is the cornerstone of this vision. The story follows a man’s investigation into strange manuscripts left by his deceased uncle, which reveal a global conspiracy of cults devoted to ancient, incomprehensible entities that predate humanity.

What makes Lovecraft unique is not violence or gore, but the philosophical premise: we live in a universe fundamentally indifferent to our existence, populated by forces so ancient and powerful that mere awareness of their existence can destroy human sanity. The true horror is not being attacked — it’s understanding our cosmic irrelevance.

This work became seminal not only for horror literature but for all of pop culture (from Alien to True Detective). It represents epistemological fear: what if knowledge, instead of liberating us, destroys us? What if there are truths that the human mind simply cannot process without collapsing?

The Thing — John Carpenter (1982)

At a research station in Antarctica, a team of scientists discovers that an alien organism capable of perfectly imitating any life form has infiltrated the group. No one knows who is still human.

“The Thing” is a masterpiece of paranoia and claustrophobia. Carpenter takes a simple concept — loss of identity, fear of the other who could be anyone — and transforms it into a visceral experience of growing distrust. Rob Bottin’s practical effects remain disturbing decades later, not just for their technical mastery, but because they visualize something deeply unsettling: the dissolution of boundaries between self and non-self.

The film failed commercially in 1982 (it premiered two weeks after E.T., which presented a much more comforting vision of alien contact), but became cult for a reason: it captures the specific terror of the Cold War — the impossibility of trust, infiltration, the faceless enemy — and universalizes it.

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde — Robert Louis Stevenson (1886)

Stevenson’s novella is so well-known it has become an archetype: the respectable Dr. Jekyll develops a potion that releases his dark side, materialized in the violent and amoral figure of Mr. Hyde. But the story is not about external possession — it’s about the duality inherent in human nature.

Published in the Victorian era, in a society obsessed with respectability and control, the work explores anxiety about what happens when social masks fall. Jekyll is not Hyde’s victim — he is Hyde. The transformation doesn’t bring something from outside; it reveals something that was always inside.

It’s cultural impact is undeniable, since the expression “Jekyll and Hyde” entered common language to describe dual personalities. But the work goes further: it questions the illusion of the unitary, coherent self that society demands we maintain. It represents the fear of internal fragmentation: what if the civilized person I present to the world is just a thin facade over impulses I don’t control?

The Sandman — E.T.A. Hoffmann (1816)

This German tale of dark romanticism narrates the story of Nathanael, obsessed since childhood with the figure of the Sandman — a creature who, according to legend, steals the eyes of children who won’t sleep. The narrative mixes childhood memories, growing paranoia, and an inability to distinguish between real and imaginary.

Hoffmann creates something deeply modern: radical ambiguity. We never know for certain if the horrors are real or projections of Nathanael’s disturbed mind. Freud used this tale in his essay on “Das Unheimliche” (the uncanny) to explore how the familiar becomes strange, how inanimate objects (a mechanical doll in the story) can evoke profound discomfort.

The work influenced all subsequent psychological literature and represents the fear of perception: what if I can’t trust my own senses? What if the reality I experience is just a construction of my damaged mind? It’s epistemological terror turned inward.

Dracula — Bram Stoker (1897)

Count Dracula was not the first vampire in literature, but Bram Stoker created the definitive archetype. The story, told through letters and diaries, narrates the arrival of a Transylvanian aristocrat in London and a group’s efforts to destroy him.

But Dracula is more than a monster — he’s a catalyst for Victorian anxieties: repressed sexuality, foreign invasion, moral degeneration, the collapse of traditional hierarchies. The vampire seduces, contaminates, transforms. He’s aristocratic but parasitic. Immortal but undead. He operates in the margins between stable categories.

This book became the template for countless adaptations because Dracula is infinitely reinterpretable — each era projects its anxieties onto his pale face. He endures because he transforms with us, always reflecting whatever we fear about change, contamination, and losing ourselves to the other.

Frankenstein — Guillermo del Toro (2025)

Del Toro didn’t just make a simple adaptation of Mary Shelley’s novel, but a meditation on compassion and rejection. The story of Victor Frankenstein and his creature is retold with the visual and emotional sensibility characteristic of the Mexican director, emphasizing not the horror of the monster, but the horror of loneliness and alienation.

Shelley wrote “Frankenstein” in 1818, but the story has never aged: a scientist creates artificial life and, horrified by the result, abandons his creation. The creature, intelligent and sensitive, is repeatedly rejected by humanity and becomes violent not by nature, but by despair.

Del Toro understands what makes this story perennial: it’s not a story about the danger of uncontrolled science — it’s about responsibility, empathy, and the consequences of treating the other as monstrous. His visual version recovers the philosophical depth often lost in more sensationalist adaptations. It represents the fear of creation: what if the real monster is our inability to love what is different?

The Haunting of Hill House — Shirley Jackson (1959)

Four people agree to spend a few days at Hill House, a notoriously haunted mansion, as part of an investigation into paranormal phenomena. But the house has a life of its own — or is it Eleanor’s mind, the fragile protagonist, that projects her traumas onto the walls?

Shirley Jackson is a master at creating terror without resorting to cheap scares. Hill House is described as “born bad,” with slightly wrong angles, doors that don’t close properly, a geometry that disorients. But the real horror is psychological: Eleanor, lonely and emotionally unstable, finds in the house a distorted reflection of her own mind.

Considered one of the best psychological horror novels of the 20th century, it influenced everyone from Stephen King to Mike Flanagan. It represents the fear of inhabited space: what if places absorbed trauma? What if there’s no difference between being haunted by a house and being haunted by one’s own mind? Jackson leaves us in ambiguity — and it’s precisely this uncertainty that haunts us.

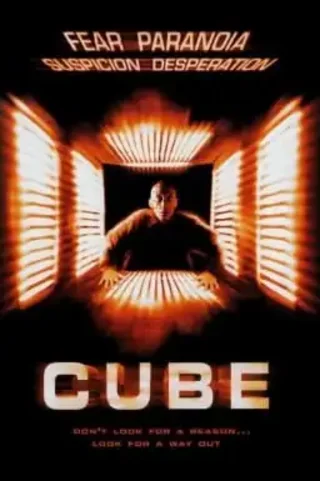

Cube — Vincenzo Natali (1997)

Six strangers wake up in an apparently infinite cubic structure, with no memory of how they got there. Each cube connects to other cubes, some safe, others trapped with lethal mechanisms. Without food, water, or explanation, they must find a way to escape while paranoia and internal conflicts destroy the group.

With a minimal budget and a single set, “Cube” is science fiction as Kafkaesque parable. There’s no explanation for the labyrinth, no identifiable villain, no redemption. It’s high-concept cinema that works because it transforms a simple idea — people trapped in an inexplicable space — into a reflection on bureaucracy, dehumanizing systems, and how extreme stress reveals (or destroys) character.

It became an instant cult classic and spawned sequels and remakes. It represents systemic fear: what if we’re trapped in structures with no apparent purpose, no identifiable creator, no clear exit? It’s the labyrinthine nightmare transported to a contemporary aesthetic, cold and geometric.

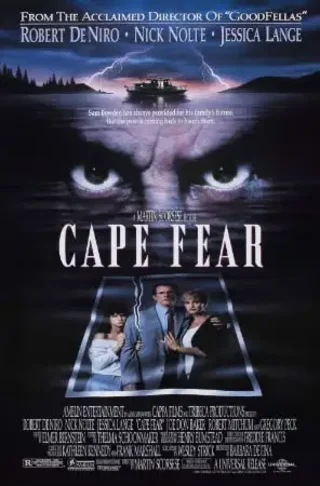

Cape Fear — Martin Scorsese (1991)

Max Cady leaves prison after 14 years and seeks revenge against the lawyer who deliberately failed to defend him adequately. Cady is not supernatural — he’s simply relentless, intelligent, and willing to destroy everything the lawyer and his family value.

Scorsese took a 1962 thriller and transformed it into a baroque exploration of guilt, justice, and how far we can go to protect our own. Robert De Niro creates in Cady a disturbing antagonist: cultured, religious in his distorted way, physically intimidating but above all psychologically manipulative. He’s not a monster — he’s what a human can become when reduced to pure obsession.

The film works because Cady operates within legal boundaries just long enough to become inescapable. Scorsese understood that the most terrifying predators aren’t supernatural — they’re patient, methodical, and utterly committed to their purpose.

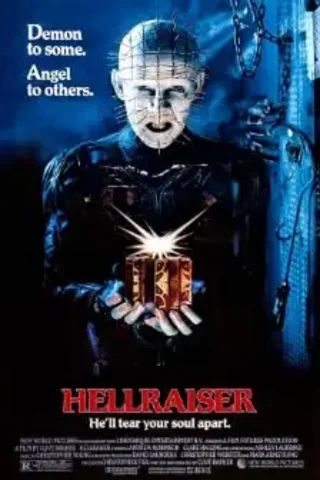

Hellraiser — Clive Barker (1987)

Frank Cotton opens a puzzle box that summons the Cenobites — extradimensional beings who no longer distinguish pleasure from pain. But “Hellraiser” is not about random monsters; it’s about people who seek extreme transgression and discover there are limits that shouldn’t be crossed.

Clive Barker, a writer before becoming a director, created a unique mythology: the Cenobites are not evil in the traditional sense — they are explorers of sensations in a realm where human concepts like “torture” have no meaning. Pinhead, the iconic leader with pins in his head, became one of horror’s great antagonists not because he’s violent (though he is), but because he represents an alien philosophy about existence and experience.

The film spawned a franchise, but the original is the better and maintains it’s disturbing power. Hellraiser represents the fear of absolute transgression: what if we cross a threshold that transforms us beyond any possibility of return?

These ten works share something essential: they all use fear as a tool for exploration. They don’t just frighten us; they make us think.

Genuine terror is not in jump scares or graphic violence. It’s in the implications, in the questions that accompany us after we close the book or when the cinema lights come on. It’s in how a good horror story functions as a distorted mirror of reality, showing us anxieties we normally keep suppressed.

Perhaps that’s why we continue, generation after generation, to seek these experiences. Not out of masochism, but because there’s something deeply human about wanting to understand what frightens us. In the safe space of fiction, we can confront our mortality, our psychological fragility, our social vulnerability. We can rehearse chaos.

This Halloween, as you revisit some of these works or discover others for the first time, perhaps the question isn’t “why does this frighten me?”, but rather “what does this fear reveal about me, about my time, about the human condition?”

Because terror, well done, is not escapism — it is, paradoxically, one of the most honest ways to look at ourselves in the mirror.